While having staff in the union does increase capacity in some ways, I had assumed that taking on more staff would mean that the ordinary members would feel less pressurised, and that burnout among them would become less of a problem. Instead what seems to have happened is an expansion of the work that everyone tries to do. Many core members still feel overwhelmed with the tasks they take on. Here are some quotes form interviews:

I do too much, it’s hard for me to say no, I end up trying to enact a million ideas as well as (formal) roles in the union. So I end up doing 50 million things, which has led to short periods of burnout.

I’ve moved in and out [of union activity], taking time out when it feels a bit much.

I often feel quite drained by [activity in the union].

So it is a common experience for core members to feel they are doing too much with the union. In an earlier chapter I mentioned the figure of the ‘highly involved activist’ in the union. Now I will look at the way in which recruitment and retention work in the union are performed in an attempt to create more ‘highly involved activists’. This is not the language that LRU uses (‘activist’ being a rather loaded term that is more often applied to ‘middle class’ people), with the community organising term ‘leader’ being preferred. But my research led me to conclude that, terminology aside, creating highly involved activists is the way in which LRU tries to grow.

In part this comes from observing the pipeline of meetings, trainings and roles that people are funnelled into when they join. Anyone who shows any willingness to do a particular task will usually be asked to take on some bigger task or role (sometimes called the ‘ladder of engagement’ in trainings). If the member is in the ‘most impacted’ category they will have a lot more support from staff to help them get involved, including going to trainings. If at each step they show willingness to go further they will often find themselves at least on their branch organising committee, possibly on the elected Coordinating Group, and both of these roles can be very time-consuming.

This nudging of people towards more and more involvement is sometimes problematised – one staff member told me that working class members were burning out from what they were asked to do. Yet it is generally ‘common sense’ within the union that this is how the union should grow. As one member said to me in interviews, “We need a mass membership of engaged members.” This seems self-evidently true in some sense, but while ‘engaged’ could in theory have a range of meanings, in the union it means investing lots of time in the reproduction of the union. As I have discussed elsewhere, this has clear diversity implications for the union.

Why did LRU choose to evolve in this direction despite wanting to appeal to people with little spare time? Perhaps the answer to that is relatively simply. As Suzanne Staggenborg (2020) points out: “Activists create the types of organizations with which they are familiar, and different types of structures appeal to different types of activists.” Much as the union has wanted to diversify, its founding and early members (including myself) were not a very diverse group. In particular, most of us were accustomed to devoting many hours a week to activism. I want to be open and say that I was involved in writing the constitution of LRU and deciding how it would be structured. At no point in that process did I suggest that we should try to minimise meetings. Rather, because my focus was on being very democratic, I probably had a tendency to suggest more meetings. I dreamed of a very democratic organisation without sufficiently problematising the work involved in making my particular vision happen.

Reasons members give for being so active are often to do with ‘self-development’, or personal satisfaction in building the union in itself.

I feel proud of the contributions I’ve made to the union. It would be a loss for me if I were to be uninvolved.

[The union] means a lot to me. […] Any spare time I get I try and do LRU stuff.

It’s a way to channel frustrations and anger, to build something different from what I find in family.

It is lots of responsibility, but I enjoy the challenge, I’ve learned a lot.

With some members finding so much fulfilment in their LRU work it seems that a filtering process has happened by which only those who want to contribute a lot of time end up being influential in the union, and they (I, or my past self) continue to perpetuate ways of working that require significant time investments.

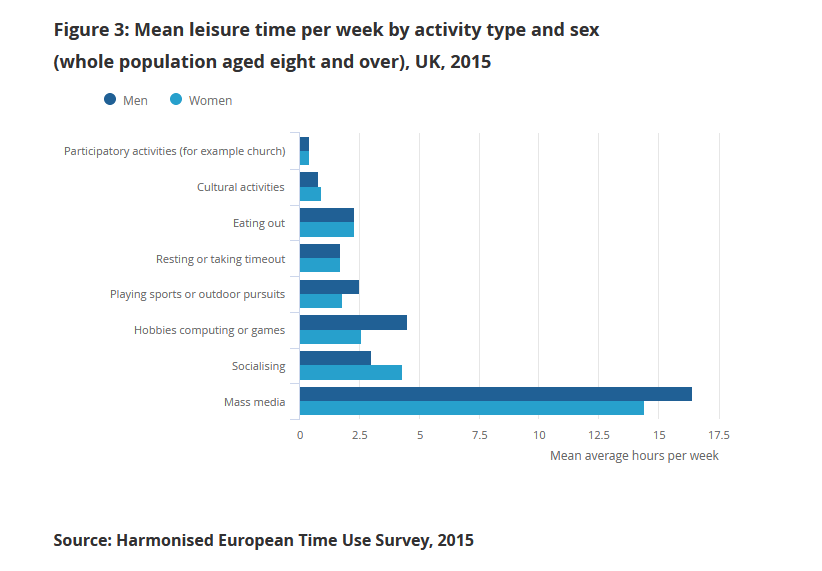

It is illuminating to look at recent statistics on people’s use of their leisure time in the UK. The category ‘participatory activities’ in the chart below explicitly includes ‘unpaid meeting time’, and though not explicit (presumably because it is such a minority activity) would likely include most other social movement activity as well.

(Sullivan and Gershuny, 2021)

So on average people spend less than an hour a week on the types of activities that LRU engages in. A lot of what they do with their leisure time consists of relaxation activities, with only cultural activities, sports and hobbies as possibly ‘higher intensity’ activities. If we make the assumption that most people don’t want to reduce their relaxation time or their physical exercise time (both being necessary for mental health in a fast-paced, sedentary society), that leaves only a few hours a week of higher intensity capacity that could be re-distributed to the ‘participatory activities’ section. Clearly on aggregate not many people do make that re-distribution, and we know that civic participation increases with economic class (Dalton, 2017), making LRU’s pitch to marginalised people even more challenging.

Adding to that is the problem that renters on aggregate have less leisure time than the majority homeowner population, as they are poorer and work lower paid jobs, and housing insecurity causes stress. Somewhat ironically LRU, having been set up as a response to the squeeze on social reproductive resources that renting entails, then asks its members to spend lots of time in reproduction of the union. Maybe it’s an act of self-care not to come to meetings! Sometimes meetings are stressful, and maybe they can often be stressful if you are already stressed, or if you are neurodivergent in a way that makes you avoid intensely social environments.

But to state the main problem clearly, the high level of participation that LRU asks of people goes against the norms of dominant culture. Some recruits refuse the invitation on the street, many who are recruited refuse the invitation once they have been to a meeting or two of the union. What, it could be asked, is the union learning from its conversations on the street and its high throughput of people who then don’t stay around and get involved? It is not clear that those experiences – for the interactions are experienced by very active members as well as the recruits – are regarded as ones to learn from.

Given the low levels of civic participation in society, is it possible that LRU is faced with a choice between being an organisation of highly involved activists or being a mass-membership renters union? It is difficult to give definitive answers to such questions, but they do offer a hypothesis for why older branches in the union have not grown much. Rather than it being about weak recruitment strategies, low resources or inadequate organising skills, could it simply be that the union is offering a life that people are too unfamiliar with and do not want, a life with little relaxation time, too intensely participatory, and too spatially challenging for leisure time activity? In a given area of London there are likely to be few people who want to take up the offer, and so perhaps branches reach a point of equilibrium where they only recruit at a similar rate to the attrition rate – which itself is fairly high for the same reasons that the recruitment rate is low.

An objection raised to this hypothesis might be that it is one of the goals of many social movements precisely to try to draw people into more political activity. This is true, but one must presumably accept the existence of external constraints to this, one of which is the amount of free time in a given society and how much of it people are willing to spend on intense participatory activities.

To head off another objection, this is not to suggest that community organising is the ‘wrong’ growth strategy, but to ask whether the union has pinned too much hope on intensive community organising as the only strategy. It has never, for instance, cultivated an ‘outer layer’ of members who are not highly involved activists but who will take action on its behalf, whether that be emailing counsellors or turning up to a protest. One might question whether a movement or movement organisation can really normalise its presence when it is mostly propagated among the limited pool of those who are willing to be highly involved activists.

There are two ways I can think of to address this problem. The first I’ll save for another blog post, but it involves LRU doing more of the activities that people already do, or need to do. Rather than asking people to step outside of the activity of their lives, LRU would try to step into others’ lives. This is a big discussion, and definitely worth another post. But I wanted to end this post with another idea.

One way to address the gulf between the lives of ‘normal’ and marginalised people and the life of an LRU activist would be to create a body of members we could call ‘LRU Reserves’, or just ‘LRU Supporters’. At present if you turn up to LRU meetings or trainings only occasionally you’ll often feel you’ve missed out on lots of things, you’ll feel out of the loop, you’ll feel an outsider. In order to avoid this we could deliberately cultivate these LRU Supporter members by suggesting they come to at least two things a year – probably mostly trainings and actions. We could offer them Get Active training, but when it’s clear they aren’t going to be very active we could suggest they come to renters rights trainings from time to time, or to the AGM, or to actions or protests. The trick would be to make people feel that what they can offer to the union is enough. Some of us highly involved members are used to the feeling that what we are doing is never quite enough, but it’s not healthy and most people sensibly don’t want to feel that. If they do feel it, they’ll disappear.

Given how the union works at the moment I think it would be helpful to even suggest this type of membership as an option to people. We’ll tell them they can be Community Organising Members (or Branch Members) or LRU Supporter Members (or whatever name we give to the group). When people opt for the Supporter role we know that it won’t be a good use of our time to try to get them to every branch meeting and every other meeting that is going on. They would only be put on a Whatsapp group specifically for Supporter members. They would get general emails from the union, and action call-outs by Whatsapp, and every few months they would get an email just aimed at them saying that there are some upcoming events suitable for LRU Supporter members. These members would feel attached to the union but would feel no guilt at failing to appear at branch meetings etc. They would identify as union members without having to look embarassed about not turning up to everything.

I think this, or some idea like this, could have a very positive effect on union growth. It would also have, I believe, a positive effect on union diversity, as it would be easier for more marginalised people in precarious work or precariously housed to feel part of the union. Would it change the nature of the union? A little, but I don’t believe it would harm the deeper community organising that we do. That could still continue with the people who have time to dedicate to it. Having an ‘outer layer’ of members would add to the union’s capabilities and reach, rather than reducing what we do. When we do a call-out for a protest or action, more people might answer the call. One day we might be able to call out enough people at just the right moment that we can ignite something big. Even if that never happens, we will have developed thousands of people who hold or at least understand the ‘LRU point of view’. This is not to be sniffed at: spreading ideas is a part of what we need to do, and if we never have the luck to ignite a big cultural moment of protest, it may turn out to be a big part of LRU’s contribution to the world.