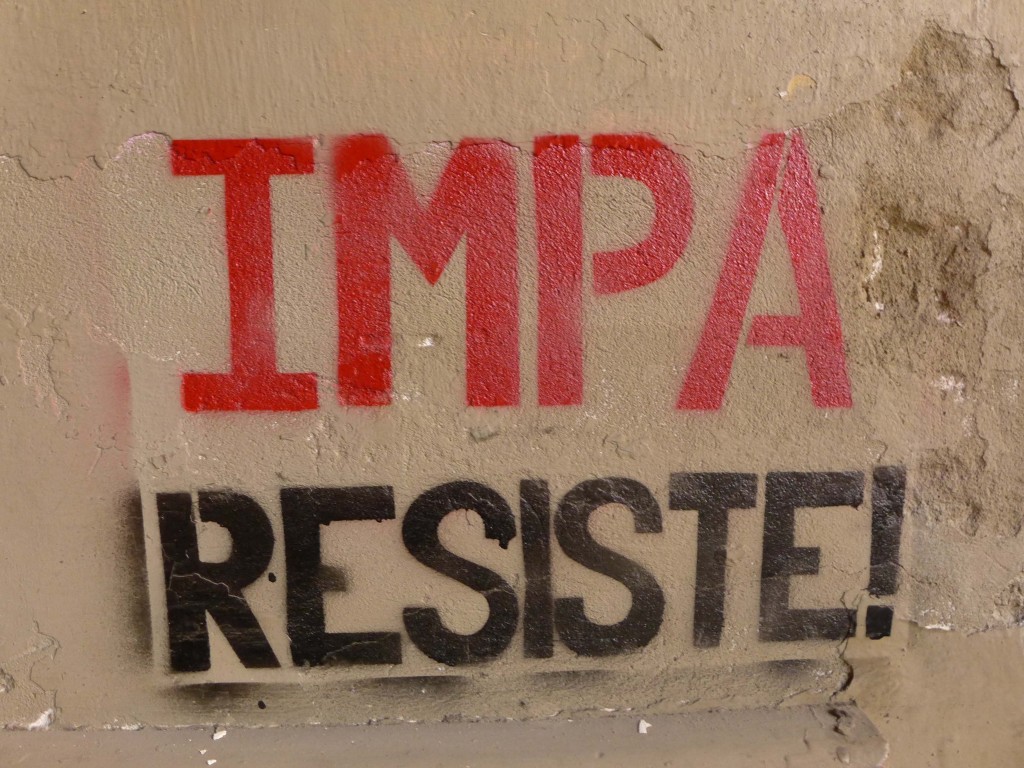

The slogan that has sprung from IMPA, one of the first factories to respond to the Argentinian economic crisis with a worker take-over, is Occupy, Resist, Produce. No part of that is easy. But the rewards are great enough that ailing businesses, usually mismanaged, are still being occupied today. I spoke to a member of another co-operative working within the IMPA factory who often joins the occupation missions. It typically involves dodging the police or security to break into a factory, or failing to dodge them. He laughs as he tells me how they helped one set of workers, all of whom were elderly, get past the fence into the factory of their former employer. The workers were too old to climb the fence themselves, but they cupped their hands for the younger activists to stand in, helping them into the property they were taking.

After occupation, the resistance begins. Owners usually want their factories back, even when they lost them because they drove them into the ground. The factory is, if nothing else, leverage for borrowing more money with which they can enrich themselves. The government and the judges are on the side of the owners of course. But not entirely, for this is Argentina, an unusual populist and corporatist state which has been supporting businesses and enterprises for years, and sees a role for itself in directing the economy but also responding to social movements. Or it used to – more on that in a moment.

There are, in theory, laws on the books in Argentina to assist workers who reclaim a factory. They can take it on as a cooperative for an interim period, as most of the occupied factories have. But it is incredibly difficult for this status to become permanent and legal, and the court decisions are often arbitrary. Most of the factories exist in a legal grey area for years, decades even, during which the risk of losing the factory again is ever-present. Campaigns for a stronger and clearer reclamation law have so far been blocked.

So within the network of occupied factories, an eviction attempt by police will result in the call going out for defenders. Many evictions have been prevented in this way. It is exhausting for those involved, but there is a strong sense of the necessity of solidarity. For the occupiers, the rewards are steady work, controlled by themselves, in an economy otherwise faltering.

To ‘produce’ part of the slogan is not easy either. The new cooperatives struggle to find the startup capital, often the workers work long hours on reduced pay for months to get factories back up and running again. And not just factories: Argentina has reclaimed restaurants and hotels too. The workers are happy to have jobs, and to have no bosses, but they struggle to get credit, and must compete in the market.

Sadly, for those thousands of workers who have freed themselves from their bosses in this way the struggle is not yet over. There are currently multiple storm clouds on the horizon. There are divisions within the occupied factory movement, as so often not just about policy but about personalities. This reduces the chances of achieving better laws and getting more assistance from the government. Some of the workers are growing older now, and the cooperatives like IMPA do not have pension funds. In a country with no public pension, they need to find a way to help their workers retired with dignity.

Most threatening of all is the new right wing government of Argentina. Those small funds available to startup coops are likely to disappear, along with the money for social programs around the factories – IMPA runs a university of cooperativism and social economics with some government funding. These cuts are looming at the same time as the ending of most protections from cheap imports, in line with the usual mandates of the neo-liberal right wing. Many co-ops, along with many traditional companies, are likely to go to the wall, unable to compete with Brazilian or Chinese products.

But it is possible that the co-ops of the reclaimed factories will be able to ride the economic waves more easily than the traditional companies. Workers struggling to save their own jobs are likely to be much more inventive and imaginative than a mere factory owner. If left to themselves they may ride out the neo-liberal market better than expected. But it is unknown how long they will be left to themselves; many Argentinians already see an increase in police repression since the new government came to power. No-one yet knows if this will result in increased occupied workplace evictions, but no-one will be surprised if it does.

It sometimes seems that for the occupied factories, including the still-not-legalised IMPA, the struggle will never be over. But they are still here, fifteen years later, still occupying, resisting and producing. The workers have no intention of giving up without a fight.