[Please note this is a personal view]

The early days of the pandemic and lockdown saw a flurry of activity in London Renters Union, along with nearly every other tenants union in the world. It was clear that people were about to lose jobs and income on a large scale and that many would have trouble paying their rent. It seemed that suddenly many renters, some of whom had been fairly comfortable previously, were about to be in crisis. In the UK as elsewhere many tenant organisers immediately began to wonder if for the first time in decades a large scale rent strike might be possible. Some people who weren’t tenant organisers also began to wonder this, and ‘rent strike’ was on many lips and typing fingertips on social media.

LRU was no exception, and many of us felt a surge of excitement at the idea of organising enough renters to have real political impact through a rent strike. So many people were affected, it seemed to us, that surely something big had to happen. Spoiler alert: there was no large scale rent strike, though it happened in a very few buildings and blocks on a small scale. This on the face of it looks like something of a failure by LRU. Everyone was so keen on a rent strike! It just needed one big push to make it happen and LRU was perfectly placed to do it! One group of London activists got impatient with how long LRU was taking to make a decision (and it’s true that slow decision-making was an issue for us in this crisis) and declared a rent strike themselves, mostly on social media. Some comrades also published a rather uncharitable article accusing the union of not having radical enough demands, as though we had succumbed to more reformist thinking without a second thought.

But the reality was somewhat different. A lot of people in LRU had been very keen on organising a large scale rent strike. We discussed it in many meetings over some weeks, filled with excitement at the thought of it. But over a couple of weeks we began to notice something rather important: when the question put to members changed from ‘do you want to see a rent strike?’ to ‘are you ready to go on rent strike?’, the answers changed from mostly yeses to mostly nos. The above article makes a lot of the agitational role of organisers in a situation like this, but the idea agitation didn’t happen in LRU at this point relies on not having experienced it as an active member. Sometimes you agitate and people won’t be agitated.

Was this due to some weakness in LRU or in the political culture of the UK? No doubt there are many weaknesses, but it is worth noting that – to my knowledge – no tenants unions in the developed world managed a large scale rent strike during covid lockdowns. This included the LA Tenants Union, who sometimes take actions more aggressively than LRU, and the Sindicat de Llogaters in Barcelona, who have the advantage of being in the most politically organised city in Europe. If even the Sindicat couldn’t organise one, maybe it just wasn’t possible. What was going on? Why did nothing larger than a block strike take off anywhere in rich countries? (I exclude poorer countries simply because it is often more difficult for news to travel from those countries to us – I don’t in fact know whether large scale rent strikes happened in poorer countries or not).

Having discussed it with a Barcelona comrade I can offer three main reasons. The first was a simple psychological factor that we as organisers did not initially consider. The pandemic was a massive disruption to people’s lives. For many people it may have been the most upheaval they had experienced in their life at any time. It was a time of either crushing losses – of loved ones, of jobs, of income – or extremely stressful uncertainty, or both. And so it turned out that the last thing people wanted to do was add more uncertainty to their lives. And deliberately inflaming the relationship on which the comfort of home depended – the landord-tenant relationship – was therefore the last thing people wanted to do. They were clinging onto whatever stability and certainty they could. Creating more uncertainty by risking hostility in and around their home was simply not on the cards. This appears to have been as true in well-organised Barcelona as in poorly-organised London.

The second reason was that relatively quickly the government acted to fend off the risk of radicalised renters. Many people were saved by the income support scheme for employers (landlords as much as renters). Many people were able to feel secure in their home for many months as a result of the evictions ban. The government also made it easier to claim Universal Credit during the pandemic, including adding a small bonus to it. What the government did not do was solve the problems of renters in the pandemic. What it did do was carefully disarm any claim that they had totally abandoned renters to their fate. The eviction ban in particular – much hated by landlords since it literally meant you could stay in the property even if you weren’t paying rent – did provide a modicum of protection to renters for a short while. Many governments in rich countries also reacted with income support schemes or eviction bans – even the notoriously anti-intervention US government managed to produce some ‘stimulus cheques’.

The third reason is that we couldn’t organise face to face. Suddenly lockdown meant that all organising was on Zoom. We achieved a lot organising this way, but to build something like a rent strike requires deep bonds of trust, it requires good relationships. It was simply impossible to do the organising we wanted to on Zoom. We were a relational organising union trying to organise through screens. I think that imposed strict limits on what we could achieve. But I do also think that even if we had been able to meet face to face, the conditions outlined in the first two points would still have been decisive. Zoom organising was only a part of the picture.

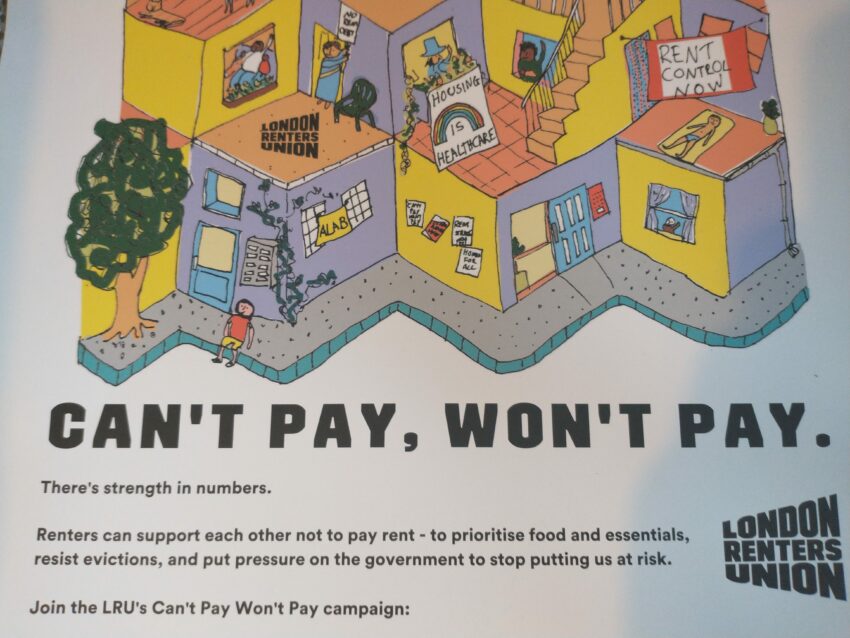

The result of all this was that the campaign LRU eventually came up with, called ‘Can’t Pay Won’t Pay’, while it did offer to support people rent striking, quickly became more focused on supporting people negotiating with their landlords, or promising to help support them in resisting eviction once the eviction ban was lifted. Even this last idea however did not turn out as expected. We thought there might be huge waves of evictions at the end of the pandemic, and instead it has been something of a trickle. The reasons for this are due to a mixture of the make-up of the renters demographic and the particular quirks of tenancy law in the UK (I don’t have enough info to talk about this issue more globally). These reasons also added to why there hadn’t been a rent strike in the first place, though in comparison to the above points they were minor. So here are some reasons I think LRU couldn’t organise a big campaign around evictions, in no particular order:

- Many poorer families in the private rented sector (PRS) were on benefits, and as previously mentioned the benefits system was deliberately made more liberal during the pandemic.

- Many other poorer occupants of PRS accommodation in London were East European migrants. Large numbers returned to their home countries. Meanwhile a big employer for those migrants – the building trades – never stopped working.

- Many other PRS tenants were younger people. Many of these returned to family homes during the pandemic, giving up their tenancies.

- Some tenants allowed illegal evictions to happen, or simply left when asked, either because they didn’t know the law or because they didn’t want to be in a home owned by a hostile landlord anyway.

- The biggest potential reason for a landlord to evict someone was rent debt. But in the UK it is rare for landlords to find it worthwhile to chase up rent debt after a tenant has been evicted, due to the time and costs of court action. This meant that many people evaded the rent debt simply by giving in to eviction. There was no motivation to resist eviction when you could effectively wipe hundreds or even thousands of pounds of debt by going quietly.

- Employment prospects post-lockdown turned out to be reasonably good, perhaps better than people expected. So people put up with small rent debts and paid them down once they were working again.

So for these reasons the ‘ticking time bomb’ of rent debt has turned out to be something of a damp squib. Some people have certainly suffered. Some certainly couldn’t get the benefits they were owed. Some were illegally evicted. Some struggled to pay back debts and suffered under aggressive landlords. But because of the government’s limited action and the six points above, all this happened on a small enough scale that it was never easy to build a big campaign on the back of it. As a result our Can’t Pay Won’t Pay campaign never went as far as we had hoped.

Could we have done more to agitate? Perhaps, but it wasn’t like some of us weren’t trying. Could we have made a louder noise? Perhaps, but remember LRU was a relatively young union at the time this hit – I often wished we’d had a year extra to prepare. What might look like a failure to outsiders looks different to insiders, who had to deal with the realities of where people were emotionally (and remember the emotions of those early days of the pandemic!) and with the various ways in which it was easier and preferable for individuals to evade conflict with their landlord rather than ramp it up.

So what lessons can LRU or other tenant organisers draw from this experience? It is the job of an organiser to agitate around a conflict, but it is clear that if the subjects of the conflict would rather avoid that conflict, and they have ways of avoiding it, they will do so, collapsing the organising potential. Those who wish to organise around a conflict then always have to look at the will to engage in the conflict and the ease of routes out of the conflict. People who are stuck in their current housing, it is clear, will be much easier to organise. In reality the Assured Shorthold Tenancy in the UK does give many tenants the chance to move relatively easily (what it doesn’t give is stability or security) and this is often the best way to avoid conflict over something about which people wish to feel comfortable – their home.

It’s a big question whether or not this is only unique to the pandemic situation in which people felt a particular need for stability in their housing. It seems to me that there is a good chance that it has implications for attempts to antagonise the landlord-tenant relationship in general. Because the problem with that antagonism is that it makes us feel unsafe in the one place where we need to feel safe. It is, I would say, even more psychologically important to feel safe at home than at work, where people often have antagonistic relations with bosses. All this would suggest that most people (as I think UK history shows) would only engage in something as aggressive as a rent strike either when they are forced into it through inability to move, or, when the landlord is a public authority that can be held in check by reputation as well as laws, and where tenancies are secure. A final exception – rare in the UK – can occur in large private blocks with one landlord where the feeling of safety in numbers can alter the balance of power not just in financial terms but through emotional support for each other.

What might that mean for renter organising? Firstly we should say that some people will always exist who will take more aggressive actions rather than evade the conflict. It certainly isn’t impossible to build some small and localised organising that doesn’t follow the above rules. In terms of large scale organising though, I do wonder if it is realistic to see it emerging around direct conflicts between tenant and landlord. That doesn’t at all mean that there’s no point in renter organising. Rather it means that we might need to think carefully about which conflicts we are trying to agitate around. It could be that it will be easier for larger scale organising to emerge around conflicts with local authorities or central government. If so we may want to turn our energies towards making that happen, rather than spending too much time pushing private renters towards conflicts with landlords that can make them feel unsafe in their homes.